Skin Cancer Diagnosis & Treatment

Full Body Skin Exams

Skin Cancer Diagnosis & Treatments | Full Body Skin Exams

Early detection saves lives. Our expert dermatologists provide thorough full-body skin exams and advanced treatment options for skin cancer.

At Clarus, we help people understand the conditions they’re facing in-depth, from their underlying causes to treatment options. For the most personalized insights and tailored treatment, it’s worthwhile to schedule a consultation.

Protect Your Skin With Expert Care

When it comes to skin cancer, early detection is a matter of life and death. The most common type of skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), is usually the least lethal. It has a five-year survival rate near 100%—if it’s detected in its earliest stages.¹

But if it’s not detected until stage 3, when it’s spread to a nearby lymph node or facial bone? That same survival rate drops to 79.3%². And if BCC reaches the 4th, metastatic stage, only 22.5% of those affected are still alive in five years³.

Other types of skin cancer follow similar patterns. Early detection can and has saved lives. It may well save yours.

To detect skin cancers in their earliest stages, it’s important to screen for them regularly. Yet, not all screening techniques are equally effective.

Considering evidence compiled from decades of data and breakthroughs, both in skin medicine and skin cancer research, the best early cancer detection technique is clear. Full-body skin exams consistently deliver information dermatologists need to detect skin carcinomas in their earliest stages—including precancerous lesions.

Cutting-edge technology and advanced techniques empower dermatologists to treat and, often, eradicate carcinomas and melanomas at their earliest stages. Better than that? Many can be prevented before they become cancers at all.

Protect Your Skin With Expert Care

When it comes to skin cancer, early detection is a matter of life and death. The most common type of skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), is usually the least lethal. It has a five-year survival rate near 100%—if it’s detected in its earliest stages.¹

But if it’s not detected until stage 3, when it’s spread to a nearby lymph node or facial bone? That same survival rate drops to 79.3%². And if BCC reaches the 4th, metastatic stage, only 22.5% of those affected are still alive in five years³.

Other types of skin cancer follow similar patterns. Early detection can and has saved lives. It may well save yours.

To detect skin cancers in their earliest stages, it’s important to screen for them regularly. Yet, not all screening techniques are equally effective.

Considering evidence compiled from decades of data and breakthroughs, both in skin medicine and skin cancer research, the best early cancer detection technique is clear. Full-body skin exams consistently deliver information dermatologists need to detect skin carcinomas in their earliest stages—including precancerous lesions.

Cutting-edge technology and advanced techniques empower dermatologists to treat and, often, eradicate carcinomas and melanomas at their earliest stages. Better than that? Many can be prevented before they become cancers at all.

What Is a Full-Body Skin Exam?

A full-body skin exam (FBSE) is a systematic, visual inspection of a patient’s skin, looking for signs of melanomas, carcinomas, and precancerous lesions. It’s also called a total body skin exam (TBSE).

An FBSE can be performed by a primary care physician, but it’s better to receive one from a dermatologist. The exam follows a step-by-step protocol to ensure no potential cancerous or precancerous lesions are missed due to their location. Each of the exam’s nine sections focuses the doctor’s attention on a different region of the body for thorough observation.

Full Body Skin Exam Process (What To Expect)

Full Body Skin Exam Process (What To Expect)

Timeframe

For most patients, a full-body skin exam takes 15 – 30 minutes. It may take longer if there are more skin abnormalities requiring documentation.

The FBSE process typically moves through four phases.

1. Preliminary Prep

Before the exam starts, the doctor will prepare you for it. The physician will explain each phase of the exam, optional positions to sit and move comfortably as needed while enabling the exam, and what tools they will use to perform the exam.

During this preliminary time, you will change into a medical gown. You may also be asked questions about your medical history and any family history of skin cancer.

2. Equipment Prep

The physician will prepare the equipment necessary for the exam. Typically, this includes bright lighting, a dermatoscope or magnifying glass, a camera to document abnormal or suspicious signs, and a notebook.

Throughout the exam, the physician will take notes quantifying and qualifying your skin’s condition. These can be referred to later if a diagnosis needs to be made.

3. Inspection

The inspection is a nine-stage process.

FBSE Inspection Process, By Segment Order

Scalp | The physician will part your hair to inspect the total scalp surface. |

Face | The physician closely examines each feature of your face (forehead, eyelids, eyebrows, nose, lips, and chin), typically with dermoscopy. |

Ears | The physician uses a tool to examine your ear canal, as well as your outer ear. |

Neck | The physician inspects the front, back, and sides of your neck. |

Trunk & Abdomen | The physician opens part of the gown to inspect your chest, upper and lower back, sides, and abdomen. You may be asked to lift your breasts and any body rolls that typically cover part of your skin. |

Arms, Hands & Fingernails | All sides of the arms, hands, and fingernails are inspected, including palms and nailbeds. |

Legs, Feet & Toenails | All sides of both legs are inspected, from thighs down to toes. Toenails and skin in between toes are also examined. |

Sensitive Areas | Sensitive areas, including buttocks and genitals, will be examined only after a second discussion of your options, and examination will proceed only with your informed consent. All parts of the genitals and buttocks with skin will be examined. |

4. Patient Education & Next Steps (Biopsy, If Needed)

After the inspection, the physician will talk to you about what they found, and the next steps they recommend. If they discover a suspicious growth, they will likely recommend a diagnostic biopsy.

During the patient education portion, it’s good to ask questions about any concerns you have. The physician may also use the education portion to offer resources on skin cancer prevention.

Signs & Symptoms of Skin Cancer

The most noticeable sign of skin cancer is an unusual lesion or growth on the skin. Often, people can detect these early carcinoma/melanoma warning signs during routine, monthly self-checks.

If you’re unsure how to perform a simple self-screen for skin cancer symptoms, try following the steps in this guide developed by The American Cancer Society, “How To Do A Skin Self-Exam.”

Whether you’re examining yourself or seeking an exam from a doctor, it’s important to know what to look for. To spot the early warning signs of cancer, pay attention to:

- New growths on your skin

- Sores that struggle to heal (or don’t heal at all)

- Patches of skin that are crusted or scaly

- Any part of your skin that seems persistently painful, itchy, or tender

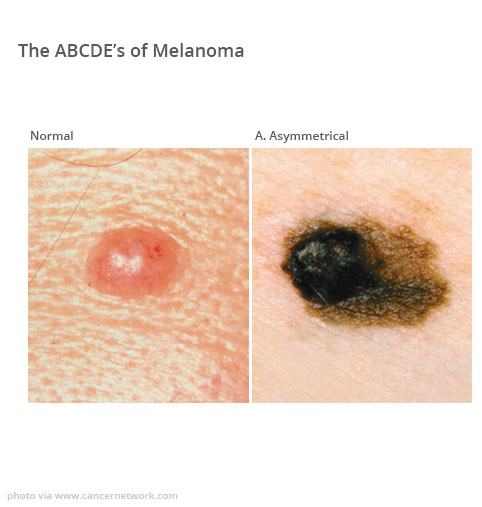

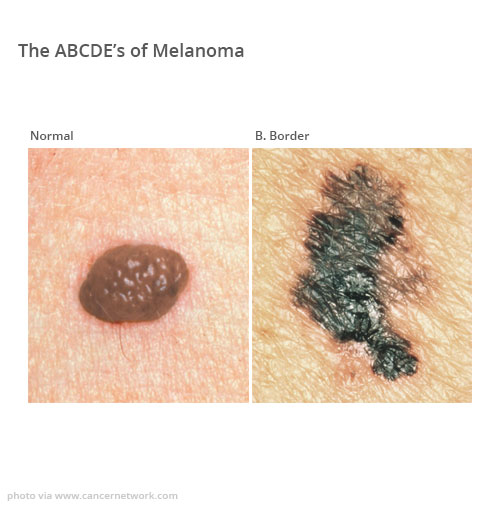

As you explore your skin, think about the “The ABCs of Melanoma.”

The ABCs of Melanoma

The ABCs of Melanoma

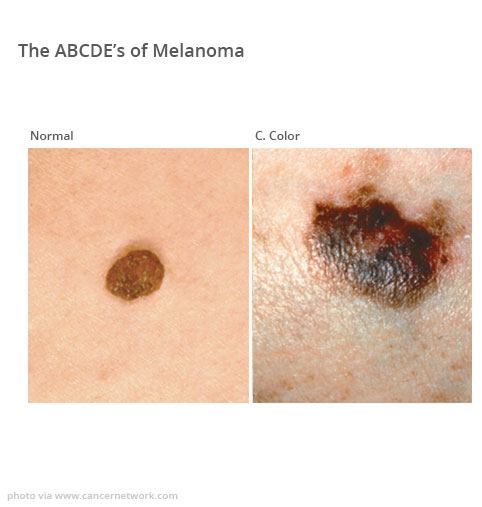

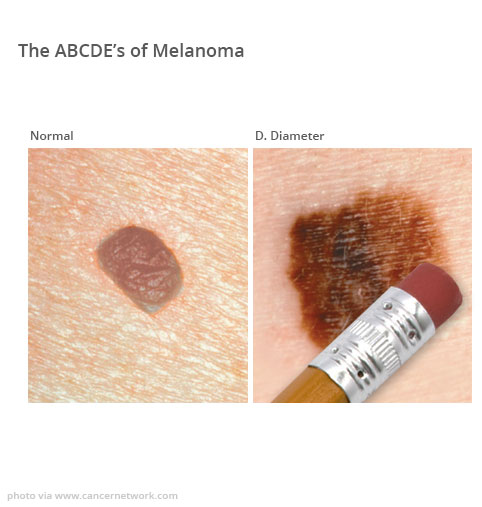

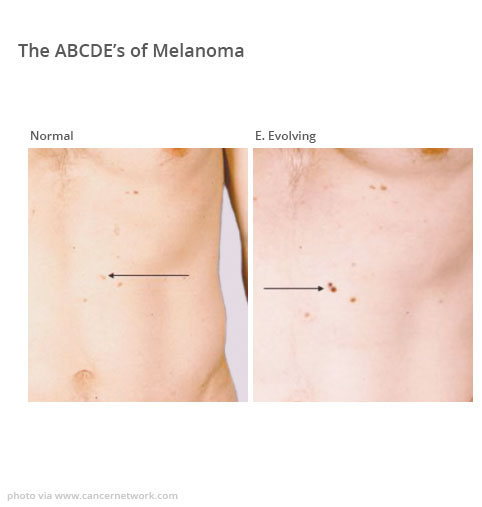

The ABCs of Melanoma are indications that a growth or lesion on your skin may be cancerous or precancerous. They are:

- A – Asymmetry: One half of the mole does not match the other.

- B – Border: Irregular, scalloped, or poorly defined edges.

- C – Color: Variations in color (brown, black, red, white, or blue).

- D – Diameter: Larger than 6mm (about the size of a pencil eraser).

- E – Evolving: Changes in size, shape, or color.

If you discover any of these markers, contact a dermatologist right away.

Understanding Skin Cancer Diagnostic Procedures

Understanding Skin Cancer Diagnostic Procedures

Determining whether a suspicious lesion or mole is cancerous isn’t something to leave to chance. If there’s any ambiguity, it’s always smart to seek out a second opinion from a board-certified dermatologist.

If a dermatologist finds anything notable during an FBSE, the next step is to investigate it more deeply. This may involve the use of dermoscopy or spectroscopy. Or, the abnormal skin feature may require a biopsy.

Dermoscopy

A dermoscope is a handheld magnifying device with polarized light. It empowers the physician to examine skin lesions in greater detail. In many cases, it helps differentiate between benign and malignant growths.

Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy investigates the skin feature using a high-frequency ultrasound. This offers insights into the growth’s density and cell makeup, which can indicate whether it’s precancerous, cancerous, or benign.

Biopsy

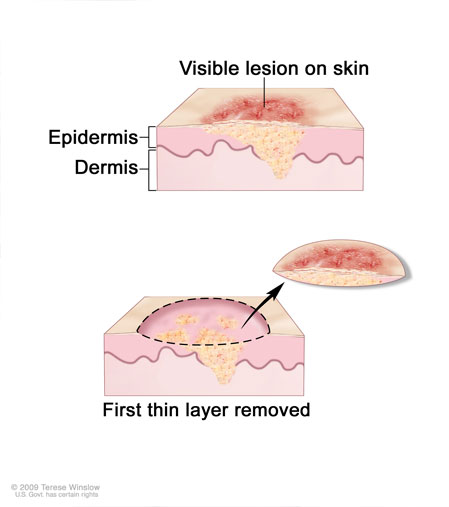

Biopsy

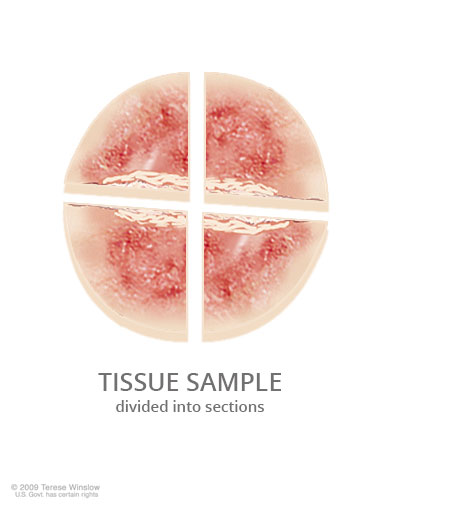

A biopsy removes a sample of the skin feature to examine via laboratory analysis. Different types of biopsies can provide different categories of information.

A shave biopsy is a superficial sample of the growth’s most external cell. In contrast, a punch biopsy and an excisional biopsy dig more deeply into the growth, extracting deeper, more internal cellular material.

A liquid biopsy involves drawing blood near the site. It can offer evidence of circulating melanoma cells.

A fine needle aspiration biopsy is only used if melanoma is already suspected. It takes a sample from the nearest lymph node to look for signs of metastasizing.

All biopsies grant critical information for diagnosis and treatment.

Skin Cancer Types & Treatments

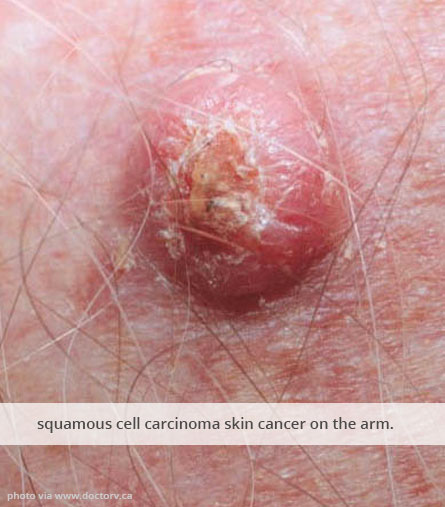

There are three types of skin cancer: basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma. Each type of cancer progresses through increasingly serious stages. So, no matter what kind you’re treating.

Our dermatologists can treat skin cancers through medical interventions, chemo- and radiation therapies, and precision-targeted drugs. Here’s what those treatments look like for each cancer type.

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

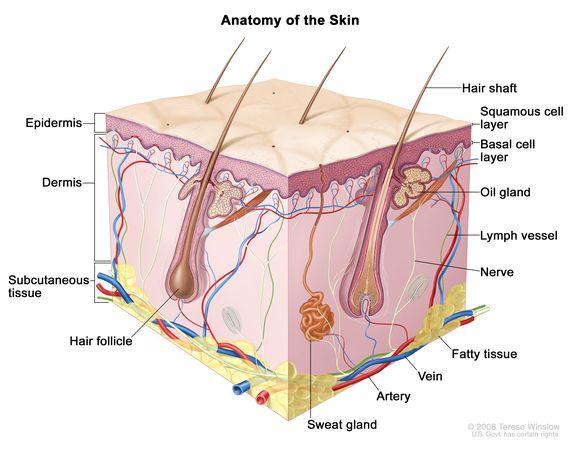

“[Basal cell carcinoma is] cancer that begins in the lower part of the epidermis (the outer layer of the skin). It may appear as a small white or flesh-colored bump that grows slowly and may bleed.

Basal cell carcinomas are usually found on areas of the body exposed to the sun.

Basal cell carcinomas rarely metastasize (spread) to other parts of the body. They are the most common form of skin cancer.”

—National Cancer Institute, NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms

Most basal cell carcinomas start as precancerous growths called actinic keratosis lesions. Actinic keratosis can also grow into squamous cell carcinomas (SCC).

Treating actinic keratosis is easier than treating either carcinoma, so if it’s found it’s important to act.

That said, since BCC starts in the outermost layer of skin, it’s usually relatively simple to remove or destroy. A wider range of treatment options have proven successful against BCC than against other skin cancers. Moreover, BCC typically doesn’t recur after treatment when caught early enough.

Targeted Pharmaceutical Treatment

Targeted Pharmaceutical Treatment

Two pharmaceutical drugs are used to treat advanced BCC specifically. Vismodegib and Sonidegib target specific pathways in BCC cells, preventing their proliferation.

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators strengthen and direct the immune system, helping it kill carcinomas like BCC. These medications stimulate the immune system’s defenses while enhancing its ability to recognize and target BCC cells.

Currently, Imiquimod (Zyclara) and Cemiplimab are the safest, most widely-used immunomodulators for BCC treatment.

Retinoids

Retinoids

Retinoids are derivatives of vitamin A. They’ve been FDA-approved as a treatment for BCC. These medicines regulate signal pathways in basal cells, promoting programmed cell death and suppressing cancerous overgrowth.

Retinoid regulation also seems to repress the hyperactivated, oncogenic (cancer-causing) pathways, preventing BCC recurrence. Tazarotene (Tazorac) is the most effective retinoid for BCC treatment.

Chemotherapy & Radiation

The most useful chemotherapy and radiation treatments for BCC are 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), a topical chemotherapy drug, and GentleCure, an image-guided, low-level radiation therapy. Learn more about GentleCure in our guide to non-surgical treatments.

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic is a minimally-invasive treatment for BCC, and it effectively treats the early stages. For more detail, please see the subsection on “Photodynamic Therapy (PDT),” which is categorized under the subheading “Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC).”

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy destroys BCC growths and lesions by freezing them. Typical cryotherapy uses liquid nitrogen or argon gas to freeze and destroy abnormal basal cells. Once frozen, the abnormal tissue swells and crusts over. Often, fluid must be drained from it, after which the tissue can scab over and slough off.

It’s an effective treatment for superficial or early-stage BCC.

Surgical Treatment Options

Surgical removal of basal cell carcinomas is the most standard treatment. Precancerous growths, early-stage BCCs (stage 1 & stage 2), and low-risk BCCs are usually removed through a standard excision or shave excision.

Both standard and shave excisions are straightforward, outpatient surgeries which cut out the carcinoma and a margin of healthy tissue.

Higher-risk carcinomas, and patients whose family medical histories or other conditions increase the complication risk, benefit from more precise surgical intervention.

One popular option is Electrodesiccation & Curettage (ED&C). This process surgically removes the carcinomas using a curette, then immediately cauterizes the incision afterward. ED&C is useful for those who are immunocompromised or have bleeding conditions.

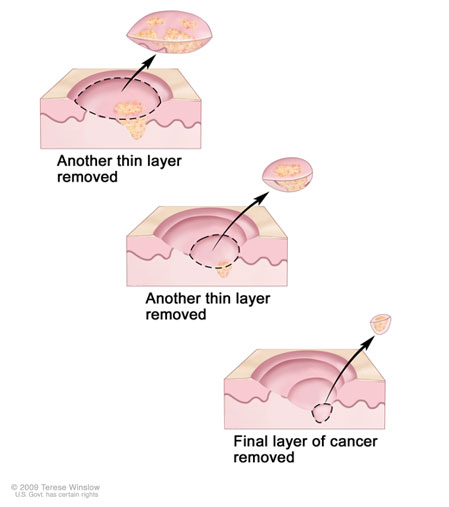

Another option is Mohs surgery, which removes the carcinoma in precise layers, using a microscope. This surgery preserves more healthy tissue. It’s also more likely to be a viable option to remove larger carcinomas.

Excising a large BCC may require a skin graft and minor surgical reconstruction afterward.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Squamous cells are keratinocytes, a type of cell in the epithelium: protective tissue that lines the body’s external and internal surfaces. Stratified keratinocytes (squamous cells and basal cells) form a protective, temperature-regulating lining in the epidermis. They secrete keratin, sweat, and sebum to serve these functions.

When the DNA of squamous cells in the skin becomes damaged, often by UV radiation, they can become a type of cancer called cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

“Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin may appear as a firm red bump, a scaly red patch, an open sore, or a wart that may crust or bleed easily.”

—National Cancer Institute, NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms

Fortunately, if SCC is caught before it metastasizes or spreads, it can usually be treated successfully. There are five treatment categories. Your dermatologist can help determine which treatment option is right for you.

Surgical Treatment

Minor, outpatient surgical treatments using local anesthesia are the first line treatment options for most cutaneous SCCs—particularly in the precancerous stage and the first two stages of carcinoma.

More complex surgeries, such as a lymphadenectomy or the excision of a large tumor, may be necessary with stage 2 cutaneous SCC if other risk factors are in play.

But, typically, complex inpatient surgical intervention isn’t needed until stage 3. SCC is in stage 3 when it has spread to lymph nodes.

Fortunately, most SCCs can be treated with these surgical interventions:

- Single-step excision: the surgical removal of the entire carcinoma, with a margin of healthy tissue.

- An outpatient single-step excision uses local anesthetic.

- The process takes 30-60 minutes, including anesthetic intake and surgical wound closure.

- Mohs surgery: the staged removal of a carcinoma under a microscope, using methods that minimize healthy tissue loss.

- It’s typically completed in a single day, over multiple rounds.

- Mohs surgery uses local anesthetic and takes 1-5 hours.

- Cryosurgery: the precise destruction of carcinomas using liquid nitrogen or argon gas.

- The process takes 10-30 minutes under local anesthetic, and most SCC cases require 1-3 sessions for full removal.

- Cryosurgery isn’t a first-line treatment, but it is useful for those who cannot undergo typical excision due to other medical conditions.

- Laser surgery (ablation): the destruction of carcinomas using an intense, hot CO² laser to destroy.

- It typically takes 30 – 120 minutes, with patients using local anesthetic or twilight sedation.

- CO² laser ablation typically treats SCCs in 1-3 sessions.

- Electrosurgery, or Electrodesiccation & Curettage (ED&C): the surgical removal of carcinomas using a curette, and subsequent cauterization.

- A heated electric needle cauterizes the excision wound immediately after removal, destroying any remaining carcinogenic cells in the process.

- An ED&C typically takes 60 minutes or fewer, uses local anesthetic, and can completely remove SCC in 1-3 sessions.

Targeted Pharmaceutical Treatment

Targeted treatments are medications that block certain signaling pathways in the targeted cells to prevent precancerous growths from becoming cancerous, shrink tumors, and prevent carcinomas from metastasizing.

Precancerous actinic keratosis, which often becomes SCC without intervention, can be treated with topical, enzyme-inhibiting creams like Tirbanibulin (Klisyri) or Diclofenac (Solaraze).

Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck can be treated with one of two EFGR-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies: Cetuximab (Erbitux) and Nimotuzumab. For certain head-and-neck cancers, IV and topical treatments can be safer than surgical interventions.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapeutic medications like checkpoint inhibitors and immunomodulators help the body’s immune system effectively detect and destroy carcinomas. Locally advanced and recurrent SCCs can be treated with Cosibelimab, Pembrolizumab, or Cemiplimab.

Chemical Peel

Chemical Peel

A chemical peel can treat suspicious, precancerous squamous cell growths by applying tricholoric acid (TCA) to the tumor. They’re safer than certain other cancer treatments.

Chemical peels are sometimes used in conjunction with chemotherapy or surgical treatment, as part of field therapy: a strategy to both remove carcinomas and, simultaneously, prevent new carcinomas from arising in the surrounding, high-risk area of skin.

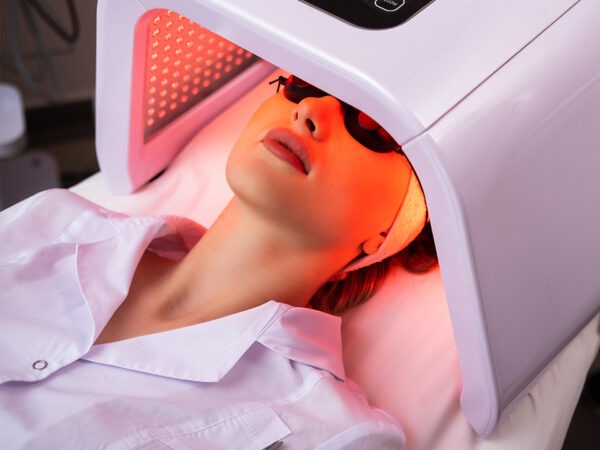

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a multi-session, minimally-invasive treatment option for precancerous actinic keratosis and SCC in situ (aka Bowen disease). It can be a safer treatment than excision for these types of SCC.

While both surgical excision and PDT are safe and effective overall, PDT carries a slightly lower risk of infection, scarring, and complications specific to patients with conditions that impair wound healing and cause excess bleeding.

Notably, PDT carries a slightly higher risk of recurrence than excision.

What To Expect During PDT

A PDT session starts with applying a topical photosensitizer (usually 5-aminolevulinic acid [ALA] or methyl aminolevulinate [MAL]) to the carcinoma and its surrounding area. Then, the photosensitizer is activated by light, typically emitted from an LED or laser. Blue light is typically used for actinic keratosis, while the deeper-penetrating red light waves are used to treat SCC in situ.

Improving The PDT Treatment Experience

PDT can be painful. Fortunately, clinical researchers have discovered different, effective methods of using PDT to treat actinic keratosis and SCC, many of which can reduce the duration or intensity of pain.

For instance, a 2021 trial demonstrated starting a blue light session immediately after applying the ALA, rather than giving the acid 1-3 hours to incubate the skin before applying the light, reduced reported pain by 30.5%.

The alteration decreased PDT-treatment pain to almost zero on the pain scale, without decreasing the treatment’s effectiveness. The less-painful PDT process destroyed precancerous actinic keratosis lesions, killed dysplastic and carcinoma-in-situ squamous cells, and prevented recurrence as effectively as the original process.

Other potential PDT alterations can include:

- Decreasing the length of sessions

- Typically, a PDT session is 15 – 90 minutes of light application after 0-60 minutes of photosensitizer incubation.

- Changing the number of sessions

- Typical actinic keratosis treatment takes 1-3 sessions

- Increasing the duration of healing time between sessions

- Typical sessions are 4-8 weeks apart to allow for healing.

If PDT is the right treatment for you, work with your dermatologist to make it as positive an experience as possible.

Chemotherapy & Radiation

Chemotherapy & Radiation

Chemotherapy and radiation treat carcinomas by killing cancer cells and halting tumor growth. Conventional chemotherapy drugs and treatments are known for their harsh side effects, as they don’t effectively distinguish between cancer cells and healthy cells.

So, dermatologists recommend treating cutaneous SCC with two cutting-edge chemotherapy and radiation options:

- 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), a topical chemotherapy cream used to treat in situ and cutaneous SCC.

- It can be applied directly to the carcinoma visible on the skin, sink into it, and destroy it—without affecting nearby healthy tissue.

- GentleCure (Image-Guided SRT), an innovative type of radiation therapy using low-level X-rays, an ultrasound, and a protective shield to treat SCC.

- Treatment is painless, and most squamous cell carcinomas can be destroyed in 6-7 weeks.

- Sessions take 15 minutes and are scheduled 2-3 days apart.

These innovative treatments allow greater precision, killing carcinomas while leaving more healthy tissue intact. They’re most effective when treating SCC in its early stages, but they can also be combined with other tactics to treat later-stage carcinomas.

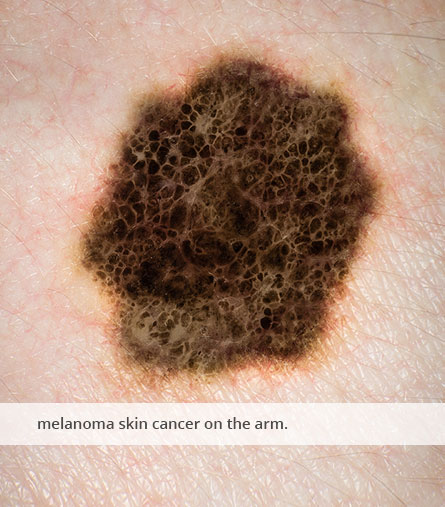

Melanoma

Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer. It grows and spreads to other organs more quickly than other types of skin carcinomas.

Melanoma is a cancer of the melanocyte cells. Melanocyte cells produce and distribute pigment (melanin), and they generate proteins that seem to modulate specific, intracellular processes involved in hearing and immune system functions.

Melanocytes are found in the basal layer of the skin’s epidermis, the vestibular organs of the inner ear, and the tissue connecting the inner ear bones.

Early detection is vital. Once melanoma is detected, there are multiple treatment options to choose from.

Surgical Treatment Options

“Surgery remains the best option for cure in localized, invasive melanoma, with an overall 5-year survival rate of 92%”

—Kenneth M. Joyce, MD, Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy

The most common and effective surgical interventions for melanoma, across stages, are these:

- Wide, local excision of primary melanoma, a single-day outpatient surgery under local anesthesia.

- It’s used to remove melanoma before it metastasizes.

- Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), the removal of melanoma layer by layer, under a microscope.

- For more details, see the description under SCC.

- Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB), the prophylactic excision of lymph nodes to prevent melanoma spread.

- It’s typically followed by Complete Lymph Node Dissection (CLND).

- SLNB is performed under either local or general anesthesia, and it typically takes 30-60 minutes

- Surgically Isolated Limb Profusion (SILP), a surgery that temporarily cuts off a melanoma-affected limb’s blood circulation to enable a concentrated, intravenous, high-dose chemotherapy drug treatment.

- The blood vessel segregation protects the rest of the body from the chemotherapy drug’s effects.

- The chemo drug can attack the rapidly spreading melanoma via the segregated bloodstream, even if the cancer has already penetrated deeply into non-skin tissues.

- After the drug has circulated for approximately 60 minutes, it’s flushed from the limb; the limb’s vascular system is reconnected to the rest of the body.

- SILP is used to treat severe, rapidly spreading melanoma in cases that may otherwise require the limb’s amputation.

- Surgical metastasectomy is the excision and removal of melanoma tumors that have spread beyond the original melanoma.

- In stage 3 melanoma, this alleviates the tumor burden and can enhance immunotherapy.

- The tumor removal reverses any immunosuppression caused by the tumors, and the surgical wounds direct the immune system to the sites of melanoma spread, enhancing the immune response against the cancer.

Immunotherapy

“The overall survival of melanoma patients has improved using antibodies targeting immune checkpoints (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4 and anti-LAG-3).”

—Dülgar, Özgecan MD, Immunology

Immunotherapeutic drugs, like monoclonal antibodies, are key to contemporary, effective melanoma treatment. These medications enhance and modulate the immune system to empower it to destroy cancerous cells.

You’ll often see these immunotherapy drugs used to treat melanoma in different stages:

- Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic virus therapeutic

- Aldesleukin, a recombinant form of human interleukin-2

- Interferon alfa-2b, an immunomodulator

- Ipilimumab, a checkpoint inhibitor

- Pembrolizumab, a checkpoint inhibitor

- Tebentafusp-tebn, a monoclonal antibody and bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE)

- Nivolumab, a checkpoint inhibitor

- Relatlimab-rmbw, a checkpoint inhibitor

Targeted Pharmaceutical Treatment

Melanoma-targeting drugs block enzymes responsible for cell growth and division, or they block the dysfunctional expression of genes signaling enzymes and proteins with those functions. The most common melanoma-targeting medications are:

- Binimetinib

- Encorafenib

- Cobimetinib

- Dabrafenib

- Trametinib dimethyl sulfoxide

- Dabrafenib mesylate

- Vemurafenib

Chemotherapy & Radiation

Chemotherapy drugs disrupt the cell cycle, preventing cancer cells from replicating. Some go beyond disruption and destroy cancer cells’ DNA, leading to cell death. Modern chemotherapy drugs are designed with features to limit similar injury to healthy cells, including:

- Instructions to target specific proteins associated with carcinomas

- Mechanisms that only affect cells in the process of division (which are more likely to be cancerous, as those cells divide faster)

- Application menthols that limit the chemotherapy drug’s effect to a specific part of the body

The most widely-used chemotherapy drugs used to treat melanoma are alkylating agents like Dacarbazine (DTIC) or Temozolomide, and antineoplastic agents like Paclitaxel.

When to Get a Skin Cancer Screening

In 2017, the American Association of Dermatologists published a comprehensive proposal detailing new guidelines for skin cancer screening recommendations.

The proposed guidelines were developed in response to the USPFT’s unsatisfactory and ambiguous skin cancer screening recommendations, published the year before.

When considering when to get a skin cancer screening, the AAD guidelines are the gold standard.

You can read the AAD guidelines in full in Melanoma Management online, or in the materials for the AAD’s free, not-for-profit skin cancer screening event, SPOT Skin Cancer™.

To quickly summarize the guidelines:

1. Every person should schedule a full-body skin exam with a dermatologist immediately upon finding a suspicious indicator on your skin.

2. Most adults should have one FBSE annually to screen for skin cancer.

3. People who face a higher-than-average risk of developing skin cancer should have an FBSE 2-4 times per year.

a. A person is considered high-risk if they:

- Have a prior history of skin cancer

- Experience excessive sun exposure

- Have skin phenotypes I or II (fair skin)

- Have a family history of melanoma

- Have a genetic disorder known to increase skin cancer risk

- Are immunocompromised or immunosuppressed

- Have been diagnosed HIV+

- Have a polyomavirus infection or HPV

4. Everyone should conduct a self-exam once per month.

Prevention Tips & Skin Health Education

There are things you can do every day to reduce your risk of developing skin cancer. Applying sunscreen, wearing protective clothing, avoiding tanning beds, and conducting self-exams can all decrease the likelihood of developing skin carcinomas or melanomas.

Apply Sunscreen

Apply Sunscreen

Wearing sunscreen is a good idea anytime you go outside. Monitor the UV index to learn whether your region is at an elevated risk on a given day.

For most people, broad-spectrum SPF 30+ sunscreen is a good choice for daily use. However, people with fair skin, an elevated risk of skin cancer, or who are planning on going swimming should use SPF 50+ sunscreen instead.

When you’re outdoors, it’s important to reapply sunscreen every two hours.

Wear Photoprotective Clothing & Anti-UVR Garments

In general, shade and clothing can help limit your exposure to UV radiation when you’re outdoors. Hats, long sleeves, and close-toed shoes are useful.

Photoprotective and anti-UVR clothing offers even greater protection than most fabrics do. If you face an increased risk of UV radiation due to your elevation, outdoor activities, current medications, or a history of sunburns, consider wearing clothes specifically designed to be Photoprotective and to block ultraviolet radiation.

Most legitimate Photoprotective clothes have the Skin Cancer Foundation’s Seal of Recommendation. These clothing brands indicate the increased UPF protection you receive by wearing any given piece. Look for clothes offering a 30+ boost to UPF.

Avoid Tanning Beds

Avoid Tanning Beds

Tanning increases your risk of melanoma. To avoid that risk, skip the tanning beds. Instead, try using a “sunless tan” product to get the glow you want without damaging your skin’s melanocytes.

The most popular sunless tan products are self-tan lotions with DHA. Studies show DHA does not increase your risk of cancer.

Another option is to apply a bronzer incorporating iron oxide. This is a great way to even out your skin tone in a way that brings out your skin’s natural browns, golds, and copper tones.

Conduct Monthly Self-Examinations

One of the best ways to reduce your risk of skin cancer is to catch abnormal growths before they become cancerous. Use The American Cancer Society’s guide, “How To Do A Skin Self-Exam” to practice the process.

Prioritize Your Skin’s Health With a Full-Body Skin Exam

It’s always the right time to take care of your skin. Schedule your FBSE online today, or call our office at (612) 213-2370.

Frequently Asked Questions

During a full-body skin exam, you should expect a clear explanation of each stage of the process. Your consent will be respected at all times, and you will be granted maximum privacy.

An FBSE is thorough and minimally invasive. Expect each exam stage to be documented in photos and notes. Photos will be zoomed in close to skin growths, and neither photos nor notes will have personally identifiable information.

You should also expect a request for your own medical history, as well as what you know of your family’s history with skin cancer. This information can help the dermatologist determine whether you’re at an increased risk of carcinoma or melanoma.

The FBSE includes an examination of skin on the genitals and anus. However, this portion can be referred out to your gynecologist or proctologist. If that is your preference, you may state that before the exam begins, or you can simply decline consent before that exam section.

Screening for cancer with a full-body skin exam takes 10-30 minutes.

Skin cancer screenings in response to a suspicious lesion or growth, and screenings of patients referred to a dermatologist by a primary care physician to address specific risk factors, are usually covered by insurance (although not always).

But, preventative, annual skin cancer screenings are not covered by most insurance companies in the United States.

Coverage for preventative care, including cancer screenings, is shaped by US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. As of 2025, the USPSTF has not recommended annual skin cancer screenings. Instead, the office has released an ambivalent statement on preventative skin exams, not affirming their value or necessity.

The USPSTF’s statement has been critiqued by dermatologists. The majority of dermatologists have found the USPSTF overlooked key benefits of annual screenings, while underrating the severity of risks of forgoing skin cancer screenings. Respected dermatologists have put forth much stronger prevention recommendations.

Unfortunately, without the USPSTF’s backing, skin cancer screenings are excluded from the list of mandatory preventative healthcare services—services insurance companies are required to cover by federal law.

As a result, Medicare doesn’t cover annual or preventative skin cancer screenings like FBSEs. Neither does CareSource, UnitedHealth, nor Anthem (through most insurance plans it offers). Cigna covers preventative skin cancer screenings, but only when they’re performed as part of an annual physical / wellness check performed by someone’s primary care provider.

That means to get insurance coverage for a skin cancer screening, you likely need a referral specifically requesting a screening and specifying the need motivating the request. This likely means a symptom noticed during a routine wellness check, or something suspicious noted by a dermatologist during treatment for a different skin condition.

If you’re concerned you may not be able to afford an FBSE, talk to your dermatologist.

When a dermatologist finds a suspicious mole, they will usually biopsy the mole to determine if it’s cancerous. If it’s cancerous, they will refer you for treatment. If it’s precancerous or non-cancerous, they may want to pursue treatment options, or they may recommend a wait-and-see approach.

Yes. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma, detected at stages 0-2, are all highly treatable. The prognosis is excellent.

When detected that early, the five-year survival rate of skin cancer ranges from 98% to 100%.

Yes. For lifestyle strategies, read our expert guides, “The Role of Diet In Maintaining Healthy Skin,” “Why Your Skincare Routine Isn’t Working” and, “How To Treat Psoriasis and Eczema In Cold Weather? 6 Tips From A Dermatologist.”

Of course, no two people have identical needs when it comes to clinical skin care. That’s why it’s so important to work with a dermatologist directly: it’s the best way to find an effective treatment tailored to your needs.